Beyond Vyshyvanka: The Art and Symbolism of Ukrainian Headwear

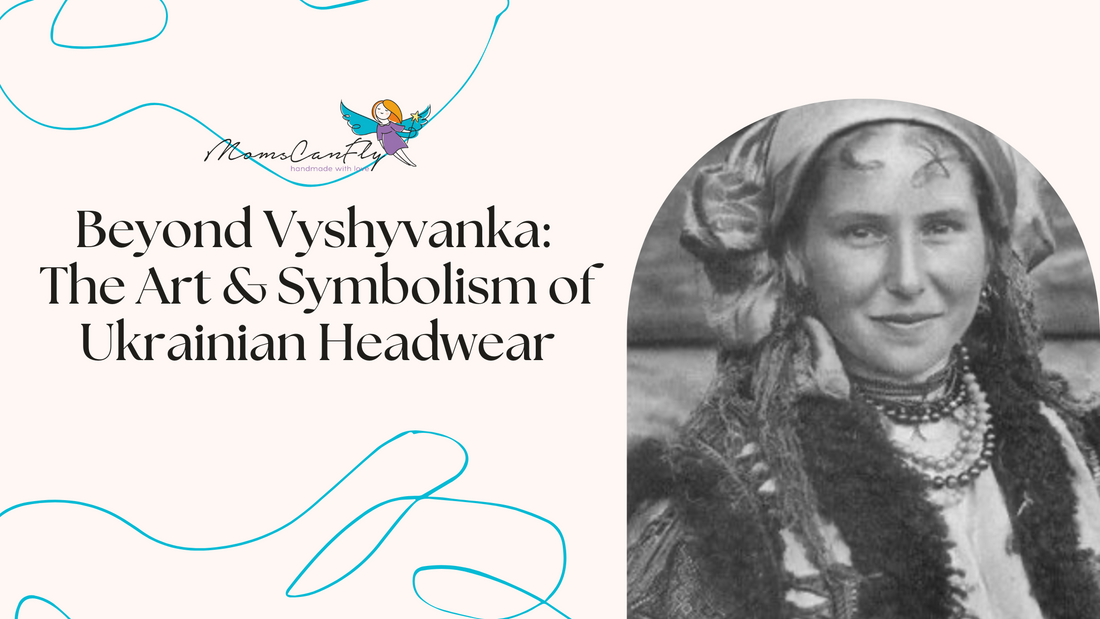

When most people think of Ukrainian folk style, they stop at the vyshyvanka. Embroidery gets the spotlight — stitched stories across shirts and dresses, proudly worn from Kyiv to California. But there’s an entire universe of tradition that starts just above the eyebrows.

Ukrainian headwear isn’t just an accessory. It’s identity. It’s ritual. It’s resistance dressed in florals and felt.

From the bold vinok (flower crown) of unmarried girls to the elegantly wrapped ochipok worn by married women, headpieces were more than decoration — they were declarations. Marital status, regional pride, seasonal rituals, even silent prayers — all coded into silk ribbons, beads, and linen folds.

And now? These ancient symbols are re-emerging. On runways. In protests. At weddings. On Instagram. Not as costume — but as continuity.

Let’s take a closer look at how traditional Ukrainian headwear evolved — and why it still speaks volumes today, even when paired with denim or Doc Martens.

A Language of Layers: The Many Faces of Ukrainian Headwear

Ukrainian headwear isn’t a single symbol — it’s a layered, regionally distinct system of meaning that traveled through centuries on the heads of women who knew exactly what they were saying without ever speaking a word. From ceremonial crowns to everyday scarves, each piece carried a story — about age, status, geography, even mood.

The vinok, perhaps the most iconic to outsiders, was more than a pretty wreath. Made of fresh or artificial flowers, herbs, and flowing ribbons, it represented youth, vitality, and the threshold of womanhood. Girls wore it for midsummer celebrations, matchmaking rituals, and spring festivals — a joyful, visible sign of purity and readiness for new beginnings.

Marriage changed the headpiece — and the message. Once wed, a woman’s hair was no longer meant for display, and so it was carefully covered with an ochipok (a fitted cap) layered under a namitka (long white cloth) or a khustka (square scarf). The transformation was not subtle. These pieces wrapped the head like a crown of responsibility — precise, proud, often embroidered or trimmed with lace. The styles varied across villages: in the Hutsul region, you’d see tall, architectural shapes adorned with coins or beads; in Poltava, soft folds and delicate silks echoed more restrained elegance.

Even within a single village, what a woman wore on her head changed depending on the season, occasion, or emotional context — a kind of sartorial language passed down from mother to daughter, woven into the rituals of daily life.

Headwear, like embroidery, wasn’t ornamental. It was autobiographical.

From Poltava to the Carpathians: Regional Identity in Every Thread

While the overarching symbolism of Ukrainian headwear connected women across the country, the details were hyper-local — shaped by geography, climate, history, and aesthetic instinct. A headpiece in Chernihiv whispered a different story than one in Bukovyna. What you wore said where you belonged, not just who you were.

In central Ukraine, particularly the Poltava and Kyiv regions, headwear leaned toward refinement. Married women wore tightly wrapped namitkas — long linen or cotton cloths wound horizontally around the head, often whitened with starch and adorned with delicate embroidery at the edges. The look was clean, composed, and symbolic of inner order — a visual echo of the region’s rhythmic folk songs and carefully balanced floral motifs.

Move west into the Carpathian highlands, and things get louder — visually, at least. Among the Hutsuls, traditional headwear became a canvas for layering: think stacked kerchiefs, coin-studded caps, thick woven sashes, and beaded forehead bands known as peremyttya. Here, the mountain setting met a bolder aesthetic. Women’s headwear sparkled and swung as they moved, especially during weddings or religious festivals, where the line between attire and performance blurred.

In Podillia and parts of Vinnytsia, married women combined ochipoks with large kerchiefs in vibrant prints, often tied at the nape or wrapped in dramatic diagonal folds. The colors here mattered — reds for protection, blues for harmony — and the way the scarf was tied could shift depending on age or status.

Further east, in Slobozhanshchyna, simplicity reigned. The ochipok remained central, but it was paired with narrower scarves, folded neatly, with minimal patterning. This region’s aesthetic was quieter — a kind of visual understatement — but no less rooted in ritual or pride.

Even the vinok varied wildly. In Volyn, it was often braided into the hair with herbs and wheat stalks; in Cherkasy, artificial flowers and colorful ribbons turned it into a lush, sculptural centerpiece for holiday dress. Some used oak leaves for strength, others wove in periwinkle for loyalty.

What ties all these styles together isn’t uniformity — it’s intentionality. Every region took the same fundamental concept — that a woman’s head is sacred, expressive, and worth adorning — and shaped it into something uniquely their own.

Crowned in Meaning: Four Styles, One Heritage

Each type of traditional Ukrainian headwear tells a story — not just of fashion, but of identity, lineage, and lived experience. The Ochipok, worn by married women, was more than a cap; it marked a rite of passage, richly embroidered to reflect status and modesty, and gifted as part of a sacred wedding ritual. Layered above it, the Namitka brought both elegance and function — a long linen wrap that balanced the rhythm of daily life with the grace of tradition, most common in central Ukraine. In the Carpathians, the Peremitka emerged as a regional signature — a boldly tied sash that echoed cultural pride, wound like a crown of belonging. And then there’s the Khustka — a soft square scarf worn by women of all ages, folded under the chin, as familiar as a grandmother’s embrace. Floral, geometric, symbolic — it wrapped both warmth and memory in a single gesture.

These weren’t interchangeable accessories. They were chosen with intention, passed down with care, and worn with quiet strength. Together, they form a visual language — one still spoken today by those who remember, reclaim, and reimagine what it means to cover the head with meaning.

The Modern Revival: Resistance, Runways, and Ritual Reclaimed

In recent years, Ukrainian headwear has stepped back into the spotlight — not as folklore, but as fuel. What once lived in black-and-white photographs or behind museum glass is now showing up in wedding shoots, protest marches, fashion week runways, and viral reels. This revival isn’t about nostalgia. It’s about reclamation.

Designers have woven traditional silhouettes into contemporary fashion, treating the vinok not as a costume, but as couture. Oversized floral crowns made of paper, silk, or even felted wool now sit confidently atop models in embroidered robes and boots, bridging the line between ceremonial and streetwear. Meanwhile, stylists across Ukraine and the diaspora have started to reimagine the ochipok and namitka as everyday elegance — wrapped in minimalist linen, layered with gold hoops, styled with blazers.

And then there’s the political edge.

During the 2014 Revolution of Dignity and again in the full-scale invasion of 2022, women began to wear vinoks and kerchiefs as quiet protest. National dress became armor. Headwear turned into a statement: We are still here. We carry our culture with us. In photo series, murals, and rally stages, the traditional wreath returned — bold, defiant, timeless.

Weddings, too, have shifted. Modern Ukrainian brides often trade white veils for vinoks made of dried flowers or porcelain, a nod to heritage that doesn’t sacrifice style. These aren’t Pinterest trends — they’re conscious choices to root joy in memory, to turn personal celebration into cultural continuity.

Even outside Ukraine, the symbolism travels. On social platforms, creators from Toronto to Tbilisi post tutorials on how to tie a namitka or layer a khustka. Gen Z wears florals not just for the aesthetic, but to connect with their grandmothers.

The revival isn’t perfect or linear — it’s lived. And like all living traditions, it shifts with the hands that carry it forward.